Defining

Budō: a path of

self-development

Budō

is a philosophy of practice centered around martial arts, but with

principles meant to extend into all aspects of one's life1.

I have been fortunate to grow up around many discussions of Budō

practice, which have helped me to recognize the pragmatic

relationship between attention, emotional control, and

self-acceptance-- as it relates to personal learning and development in

general. As a student of aikido, as well as the art of teaching (currently working on my

PhD in Education), I find my Budō

study extended by classroom teaching experiences, and my teaching approach

likewise guided by that 20-year martial experience of the

body-mind-spirit as a unified center of learning.

Being “alive”—growing,

feeling, responding, desiring, adjusting, and learning—is a state

naturally filled with discomforts, changes, and imposed conditions.

Individuals often obsess over these challenges, making them into fuel

for suffering: they focus on that mental/physical discomfort, that

impermanence of phenomena, those objects and events that make certain

things happen or prevent other things from happening (my sensei

refers to this approach as “victim mode”). But they may

alternately observe these challenges as tools for study: approaching

every difficult, unexpected, or non-ideal experience as a sensation

to be present in, a change to acknowledge and adapt to, or a

situation to accept and respond to (my sensei calls this approach

“solution mode”). Whether facing an intellectual challenge or a life-and-death challenge, this latter mode of relating with the world supports growth, health, and positive learning (as opposed to stiffness, numbness, or avoidance).

Foundation-work:

concentration practice and awareness-building

The first step toward a

solution-orientation—toward realizing one's capacity for dealing

with life's difficulties—is exercising awareness. Awareness, my sensei explains, is

a byproduct of concentration (i.e., focused attention): for example,

by focusing on the punching hand, one may develop a strong punch, but

then notice that they have been neglecting their hikite (the

hand that pulls back to bolster the punching hand). And as one brings

attention to making a stronger hikite, their punching hand remains in

their awareness – and so on as they move to lower their raised

heel, or draw back their too-high chin – each time bringing a new

area into their awareness.

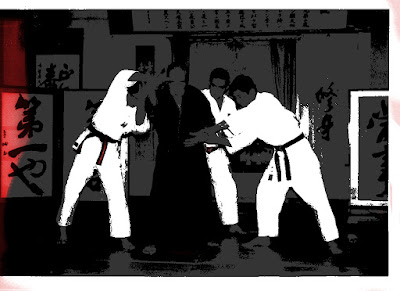

Budō

practices within Aikido, such as Jiyu/Chikara Randori

(responding to unplanned attacks with situationally appropriate

defenses3)

and meditation (mindfulness training), tacitly demonstrate to the

practitioner that awareness

is a present-moment state of consciousness—not only of one's

rational sense-making thoughts about the external world, but also of

one's motivations and emotions, which underlie those

internally-constructed stories.

For

instance, within a typical meditation session, individuals (1)

conduct a full body scan – moving their attention systematically

through all regions of the body, from the top of the head, through

the front and sides, the core and limbs, down to the tips of the toes

(and often holding attention at points that could be rushed or

neglected – the chin, fingertips, etc.); then (2) notice sounds –

far sounds (birds, street noise), near sounds (floor creaks, shutters

moving), internal sounds (breath, pulse, heartbeat), but “making no

particular effort to listen”; and after settling into that calm,

situated awareness of self, (3) focus on breathing – counting each

inhale and exhale, and as distractions arise, staying present enough

to “let them come, let them go”: this trains the mind to approach

thinking analogously to breathing, not

as a desired object to hang on to distractedly, but rather as a

passing experience to be fully present in4.

An

important part of such mental practice is dealing with physical

discomforts—itches, numbness, joint pain—by studying it (“What

kind of pain is it? Dull, sharp, throbbing, steady?”) rather than

making stories around it (“Poor me. I'm so unlucky. Why is sensei

torturing me with this stupid practice?”). In this way, mental,

physical, spiritual exercise is one same study: a practice of

presence, where one's spiritual motivation (that genuine, felt

purpose behind one's training) shapes one's mental attitudes and

thoughts (those translations of direct experience into emotional and

rational mind-states), and thereby one's actions (those areas

attended to or ignored, words spoken and their tones, those actions

taken and their manner).

The principle

of such mental and physical study is learning to recognize and

control one's real-time responses to sensations, emotions, and

thoughts when difficulties arise. Though one's success from day to

day is expected to vary with one's energy level and focus, the aim is

always the same: do your best, always. And the way to that is hard,

but simple, work: developing principled awareness.

Mastery-work:

attitude refinement and experience-building

After the basic

level of using focus on breathing to calm the body and mind,

smoothing the agitations in one's perceptions5,

an individual can move to more advanced levels of practicing

concentration, deliberately turning common distractions into objects

of meditation:

- observing pains (e.g., noting the sensation as a helpful signal, managing it),

- resolving thoughts (e.g., addressing a guilty or angry memory by walking through that situation and picturing what one should have done, or can do now to move forward), and

- balancing emotions (e.g., evoking more broad-minded attitudes {equanimity, compassion, wisdom} to move one's feelings beyond survival-mode attitudes {desire, greed, aversion, ignorance} and the self-obsessed boundaries that those strong likes and dislikes construct between us and our environments).

In

this way, meditation provides an opportunity to attenuate the effects

of emotions like fear, surprise, worry, and doubt (the four “diseases

of the samurai”) and expand to different levels of perception by

developing one's power of concentration. The practice of martial arts

techniques, likewise, extends training of these abilities—either

through solo practice, or with partners—as a type of “meditation

in motion.”

The

Human Value of Budō: a

personal, practical, principled existence

These

budō

practices—alongside family interactions, work challenges, and

myriad other experiences in life—can all be approached as tools for

developing wise attention

– that is, “seeing that is based on awareness,” This ability,

to be present in experience, enables a person to bypass disruptive

emotions and distracting thoughts (tomorrows worries, or yesterday's

unrelated dilemmas) and to focus purposefully on the current

situation.

Bringing

oneself to a presently aware mental state provides an opportunity for

responding by appropriate means

– that is, “kind, respectful, truthful, and timely action.” And

through repeatedly engaging with experiences in this principled way,

one can develop a foundation of practical familiarity and confidence

across situations, nurturing the personal inclination to respond to

life's difficulties with a “right and sharp” internal state; with

ever more self-transcending states of mind:

- equanimity – “maintaining an impartial mind in the midst of life's changing conditions,”

- compassion – “a certain sense of responsibility for other people” based in appreciation for others' existence making our existence possible, and

- wisdom – “knowledge in service of the heart … [where] the heart tells me what I should be doing (the principle of mutual welfare and prosperity); the brain tells me how I can get there (the principle of maximum efficiency).”

These

mental states encompass emotions, motivations, and thoughts; they

help the individual to stay solution-oriented: to develop strength,

empathy, and prudence in practice. And they are simultaneously

personal, practical, and principled in nature: based in one's

individual first-hand experiences with the world; oriented toward

dealing effectively and efficiently with such experiences, given

one's traits and inclinations; and directed by a sense of being that

is connected to one's environment, humbly sustained by that

environment, and ultimately given meaning in life by supporting that

larger ongoing existence.

*

The

Place of Budō in Education

I have both

seen and benefited from the efficacy of budō's

holistic mind-body-spirit approach to individual self-improvement.

And for me, as an educator and educational researcher, budō

underscores the interconnection between personal and professional

development in learning-centered environments—with important

implications for educational practice, personal learning, the process

of becoming a teacher, and the nature of the teacher-student-subject

relationship:

Regarding

educational practice –

everyone's experience is naturally filled with highs and lows, both

internal (our fluctuating “receptive states,” e.g., emotional

control, clarity of thinking, motivational energy-level) and external

(the incoming “vicissitudes of life,” e.g., pleasure/pain,

gain/loss, praise/blame, fame/disrepute). Avoiding the discomforting

lows limits full awareness and the growth of wisdom: this means that,

if learning and personal growth are primary goals, then fluctuations

in daily performance should not be seen as permanent guarantees nor

as discouraging limits, but as valuable feedback—that informs

ongoing personal development and learning over time.

As my

sensei once explained,

“We are all humans; we all have our highs and our lows. But if,

during your lows, you allow discouragement to set in, you begin to

lose control. This is why there are certain words that we do not say

['try', 'quit', 'wrong', 'forget', etc.] … If you say 'Sensei, I

won't quit,' … the word quit

is already in your head; you are already struggling not to quit.”

Regarding

personal learning –

one's body and mind are intimately entwined, likewise one's emotions

and thoughts. This means that an individual's perceptions

are influenced by their sense of self, and their current attitudes

toward a lesson / activity / social atmosphere can and will influence

what they learn from those objects of study in a given situation.

Thus my sensei offers reminders like this: “Don't take it [an

explanation, a correction] personally; if you take it personally, you

will miss the lesson,” and “If you say in your mind, 'I cannot do

this; I am finished,' sure,

you are finished [before you move],” and mantras like these:

“Challenges make me think, thinking makes me wise, wisdom makes me

free,” and “Familiarity is the antidote to fear.”

Regarding

the teacher's role and becoming a teacher

– teaching is essentially a continuation of learning, where an

individual uses their own learning experiences and understandings to

help and guide others who are studying and developing in that area.

This position of leadership requires constant refinement of technique

(what one knows), method (how one teaches others), and character (how

one feels, thinks, and acts), since a teacher's core

educational tool is him/herself:

each acts uniquely as a living example of a school's / discipline's

standards, values, and practical possibilities.

Teachers

offer personal insight, through all modes of expression: “There are

many ways to explain, but the best is through your own actions.”

They offer guidance, again, in both actions and words: “A teacher

who wants his students to develop will say, 'Don't do what I do;

start from here, and eventually you will get to where I am, through

the process of development.'” And they offer reassurance, once

again, through words and actions in concert: “We place higher

demands on our top students, not because we want you to be

a certain way, but because we want you to be able to say to those you

teach, 'I went through that.'”

To

make immediate and approachable a subject that sometimes seems

distant and ungraspable to an inexperienced student, a teacher must

understand not only their subject, but the experience of learning

that subject deeply. Thus, explained the founder of Yoseikan, Minoru

Mochizuki: “A teacher is a student who teaches in order to continue

his study.”

Regarding

the teacher-student-subject relationship

– teachers and students are connected through the shared learning

of a common subject: their dō

or 'path' – an experiential term that implies both the impersonal

direction (e.g., dojo,

literally 'Place of the way,' a school; or Aikido,

literally 'Way of combining forces,' a particular field of martial

study) and the personal journey (e.g., budō,

literally 'Martial path,' the life-study of martial arts; as opposed

to bujutsu,

literally 'martial technique,' which focuses on technical study

without incorporating self-development).

Together

on this learning-centered path, a teacher's (ideally: wise) guidance

tests the students with purposeful challenges, and the students'

(ideally: effortful) struggles reciprocally challenge the teacher, as

both develop deeper, more abiding individual connections to that

subject. Each takes on a distinct, but synchronized role in shared

development of learning: “I cannot do it alone,” my sensei

explains, “a teacher needs students. But between teachers and

students there is always a path … and just because we are all on

the same path does not mean we will step in the same places.”

*

The

work of learning, and the art of educating—in whatever subject,

along whatever path—fundamentally requires the development of self;

the discovery, refinement, and sharing of that self; the cultivation

of a personal (sincere), practical (experienced), principled

(purpose-driven) character. Without that stable center, that human

heart, 'knowledge' is but an empty symbol, 'philosophy' but a shallow

pretense of virtue, and 'strength' but an artless force. And with

that human heart, knowledge and kindness and strength fill with a

single meaning (a purpose-driven life) and lead toward wisdom.

As

William Blake once wrote, “The road of excess leads to the palace

of wisdom.” If I had to turn this dauntingly long reflection into

a mantra brief enough for an educator's out-breath, it would probably

be this.

The

Way of Education: a haiku

“Do

not try; do your

Best, as yourself, and that

Much you will become.”

Best, as yourself, and that

Much you will become.”

– Josh

Kuntzman (15 March 2016)

1 As

my sensei's teacher, Minoru Mochizuki, once explained in reply to

his question, “What is the purpose of aikido?”: “It's learning

to deal with life's difficulties, isn't it?”

2 In Yoseikan Aikido, my sensei since the age of 12

3 The

difference in Randori: jiyu is for technical study, chikara

is for developing control and

effectiveness under duress.

4 My sensei

emphasizes here that the individual should both note a distraction

itself – labeling it “distraction” – and acknowledge the

tone with which one notes that distraction – was it with “anger,”

“impatience,” “amusement,” “acceptance,” etc.

5 (“like

the surface of a lake,” letting turbid particles settle down and

hidden objects float to the clear surface)

No comments:

Post a Comment